Film Screening 13th November, 2015

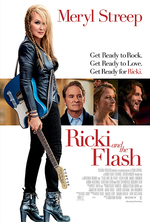

Ricki and the Flash

7:30 PM, 13th November, 2015

- PG

- 101 mins

- 2015

- Jonathan Demme

- Diablo Cody

- Meryl Streep, Sebastian Stan, Mamie Gummer, Kevin Kline

Multiple Oscar winner Meryl Streep is a cinematic legend. We are all aware of her power and prowess. She is well respected for her choice in roles and has changed the perspectives of how women are represented on screen. She is not afraid to play ‘the bad guy’ or complex, well-developed characters.

Ricki and the Flash offers a seldom explored theme in cinema – women who don’t want, or aren’t ready, to be parents.

Ricki is a musician who gave up everything to follow her dreams to be a rockstar. She chose to follow her passion and left the responsibility of raising her children to their father. When a crisis hits, he asks for her help and she returns home to see how her family has moved on without her. This film delves deep into heavy topics: the role of women, family dynamics, heartbreak and redemption.

Acting opposite her real-life daughter Mamie Gummer (who conveniently plays her on-screen daughter), Meryl Streep’s portrayal is perfect as the tattooed, reluctant mother and guitar-slinging goddess. She is a free spirit who oozes rebellion and sex appeal. Streep pushes boundaries in this film and, not surprisingly, proves that women – both fictional and real – can be passionate, complex and wild creatures at any age.

Elyshia Hopkinson

Coming Home (Gui lai)

9:21 PM, 13th November, 2015

- PG

- 109 mins

- 2014

- Zhang Yimou

- Zou Jingzhi

- Gong Li, Chen Daoming, Zhang Huiwen, Li Chun

Dalton Trumbo once said of the Hollywood blacklist era that there were no heroes or villains, only victims, and that’s how China’s Cultural Revolution is presented here.

We open with news that Lu (Chen), a political prisoner, has escaped. The news affects his two family members very differently: his wife, Feng (Gong), longs for his return while his daughter, Dan Dan (Zhang), longs for him to stay away – for the sake of her career as a dancer. She gets her wish when Lu is recaptured.

Years pass; Mao dies; Lu is exonerated and returns home. His wife has never moved on, nor forgiven her daughter for her role in Lu’s re-arrest, and she’s lost both sanity and memory: having twice had her husband snatched away, she’s living in a world in which Lu is still about to be released from prison, and can’t believe it’s actually him when she sees him.

If the world were fair I would only have to tell you this film was directed by Zhang Yimou and nothing could keep you away.

China’s most internationally renowned director, his films are always beautiful, whether they’re intimate sketches (Not One Less), the most outrageously elaborate martial arts spectacles you’ve seen (Curse of the Golden Flower), or something harder to describe so neatly, like this. It’s a revelation to watch – a uniquely subtle melodrama.

Henry Fitzgerald